A prototype build-able AR gallery of non-human visitors to one 3x3m space over 24 hours

In an attempt to share the concepts of connectedness and promote democracy of space by revealing a series of otherwise invisible actors through a hidden camera, I chose one of the many physical intersections where human and non-human regularly interact in the landscape. This interaction if only through aesthesis – smells, sounds and traces on the ground speaks of our connectedness. Over time, I studied the sharing of this space by both human and non-human (Fig 1) and collected evidence of how each actor influences each other’s behaviour: How humans are avoided, how the birds steal the twine for nesting, where the badgers reroute to avoid tractors for instance. Connecting us through one camera lens over a 24-hour period, my aim was to direct a spotlight toward connectedness through space-time highlighting the union of things through space and over time (Fig 2). Making-kin is central to this piece as is the potential to uncover tangible entanglements.

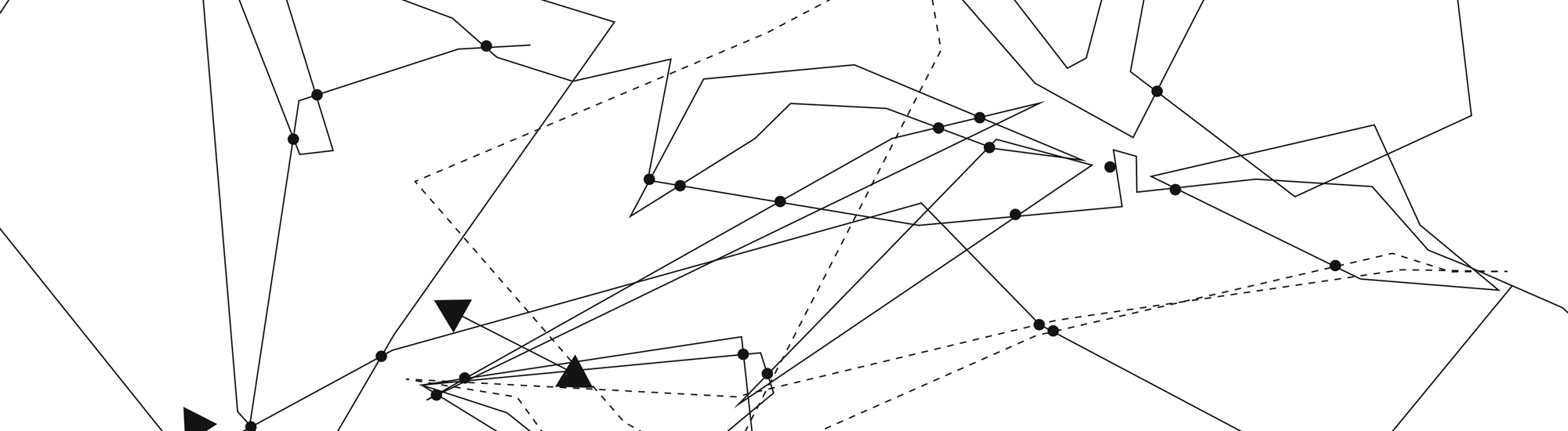

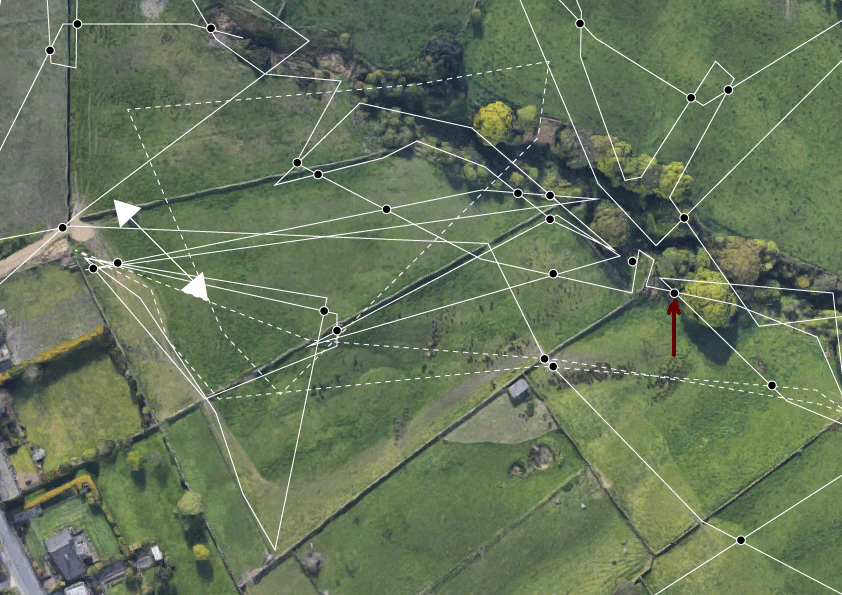

Over a period of a few weeks, I logged transient and geomorphic changes in the landscape where there was movement and the presence of non-humans. Each line represents the traces of paths created over time. Transient dew lines are mapped with dashed lines with the black dots highlighting intersections where ‘we’ were copresent through time. The intersection I chose to film for the project ‘One Small Space through Time’(see Fig.2) is highlighted with a red arrow..

Fig. 1, Mapping the Intersections (2021)

Fig. 1, Mapping the Intersections (2021)

Fig. 2, Composition of 24 hour traffic at the intersection (2021)

Fig. 3, The union of actors – Tangling the occupants through one continuous line (2021)

By investigating intersections of entanglement, there is an opportunity to illuminate the perceived-invisible or ignored socio-natural relations. Focusing on landscapes where affordances, agents and their traces in the landscape become the embodiment of the narratives of the human and non-human lives that have shaped them. In creating a union of actors (Fig 2) within a given space over time there is an opportunity to reveal otherwise hidden connections with the aim to add value to the environment.

A prototype AR installation to further amplify the position of each actor on the stage seeks to re-connect human and non-human through shared space-time (Fig 4 & 5)

Fig. 4, SpaceLog: Viewing the viewer of the experience

Fig. 5, SpaceLog: In Camera view

Research and Written Study for the Intersection of Kin:

Finding better ways to inhabit our story of destruction.

How do we repair the harm we have done to the Earth? It is imperative that we do so, but first we should remember that it is not the Earth that is broken but our relationship with the Earth.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, The Covenant of Reciprocity (2017, p. 369)

Introduction:

In an article written in 2018, Vybarr Cregan-Reid considered why the chair should be viewed as a universal signal of the arrival of the Anthropocene. The humble chair, of which I own nine variations, has transcended its origins as a luxury afforded to the rich and powerful to become a basic necessity of modern life on earth. This article illuminates the irony of persisting in our desire for comfort with 75% of our time spent sitting, in the knowledge that inaction is killing us. (Cregan-Reid, n.d.) As a species, we widely recognise the modus operandi of our anthropocentric world: we know that certain actions are causing an individual, societal and environmental crisis, yet we largely continue to remain blinkered in the face of imminent destruction of ourselves. We are sat firmly in the proverbial rocking chair, in a paradox, where we are displaying a profound disentanglement with nature, the very thing that secures our future. We, I, do this with a feeling of hopelessness. How can we possibly fix the problems we have created? Do we remain blinkered and powerless to things beyond our control or find a way to move forward? How do we cut ties with anthropocentrism to find a way back to multi-species connectedness?

This study, conducted through an ecocritical lens, seeks to examine the discourse on our species and the environment where the focus is on our connectedness with nature.

In an attempt to avoid a declensionist narrative where destruction and decline fuel hopelessness, my aim is to explore through making, storied landscapes and enlightened imagery and to provoke and promote kinship with all matter of things. Through practice, I aim to enjoy a celebration of hybridity where connectedness with nature thrives through space-time and tests the perception of us as ‘individual’.

As an individual, when it comes to accepted discourse surrounding what have been described as ‘wicked’ problems – those problems such as climate change and mass extinction where the problem is described as a symptom of other problems that cannot be solved (Rittel and Webber, 1973), it often feels impossible to conjure a positive outcome for the future. We live in a world of infinite nature-culture collisions, yet we still consider ourselves as distinct from our environment. And whilst there is no single manual to help us move toward an equitable sharing of future landscapes or a re-balancing of power, it has never been as important as it is now to find ways to illuminate our connectedness to all things.

With notions of connectedness comes entanglement described as a phenomena ‘where the behaviour and properties of parts of a complex whole cannot be described and understood independently from the behaviour of the other parts (and of the complex as such)’. (www.torch.ox.ac.uk, n.d.).

To be entangled with nature, to be part of that ‘complex whole’ is to be part of a democratic society for all manner of entangled things. This idea underpins an emerging theme in my work of ‘making kin’ (Haraway, 2016) yet in the wider world the ‘democracy of all things via entanglement’ as I will call it, remains a somewhat utopian concept. In a simpler description of our connectedness, philosopher Timothy Morton states, ‘we are nature’ (Morton 2018) and with that gut-punch of an explanation, entanglement is no longer a more complex form of connectedness but a phenomenon outside our control. This idea, alongside the promotion of ‘making-kin’ described in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene by Donna Haraway remains front and central to all that I read and make.

It has become clear during this study that in order to adequately address our inability to save us from ourselves and maintain a secure future environment, our relationships with nature need to change.

Using this premise and the highlighted issues and insights as a springboard, I aim to explore ways through research to encourage relations to the non-human world and through practice address our weakening connection with nature. Through this exploration, I will confirm notions of the human-nature concept, highlight emerging barriers to connectedness and encourage the revelation of entanglement through art and the strategies I employ to provoke reflection.

Chapter 1: We Are Nature

In Western society I think it is fair to say that there is a widespread failure to recognise, understand and appreciate that we are not only connected and dependent upon nature, but inevitably entangled with it. We are an influential and integral cog in this complex system that is referred to as ‘nature’ (West et al., 2020).

Despite the notion that ‘we are nature’ (Morton 2018), human divergence from the natural world seems to be linked with technological developments in the 19th and 20th Centuries and through the proliferation of capitalist and consumerist societies. From our cars, workspaces and homes we are increasingly sterilised and sheltered from ‘real’ nature and the impact of our increasingly violent climate. Fuelling the little discussed and emerging problem of Biophobia, is our tendency to physically separate ourselves further from nature. E.O. Wilson in ‘Biophilia, The Diversity of Life’, argues that the ‘decline in biophilic behaviour will remove meaning from nature’, resulting in a ‘loss of human respect for the natural world’ (Wilson, 2021). We could say that this is happening right now, amplified by the germs of a pandemic and our inability to face the looming crisis of self-destruction.

Yet within us, within me is a deep desire to connect with what we widely understand as ‘nature’. Described as ‘the passionate love of life and of all that is alive’ (Wilson, 2019), Biophilia is widely accepted as an innate trait and one that has helped us to evolve. Biophobia in contrast has innate beginnings in that it protects us from danger, yet it is amplified by social and cultural influences.

As a barrier to conservation efforts, Biophobia is on the increase (Olivos-Jara et al., 2020) with entanglement, connectedness and enactivism being reduced to a primordial echo. Living in an anthropocentric environment not only encourages a sense of superiority and control over non-human things, for some it creates a physical and psychological barrier from the very thing that they are.

In a body that holds almost 2kg of bacteria, yeasts, fungi, viruses and protozoa, a huge ecosystem of complex organisms (WEF, 2018), perceiving ourselves as ‘individuals’ and claiming to be physically departed from non-human things is factually incorrect. But the very nature of biophobia suggests a psychological response at odds with the very essence of ourselves.

In exploring our innate responses to nature, we cannot ignore the term ‘Anthropocene’. Defining the Anthropocene as an accepted concept as well as an epoch is testament to both our indisputable entanglement with nature and the growing unease and horror of our impact upon this world and the power and ability, we have to irreversibly change it. The commitment to investigating relationships between human and non-human cultures where emphasis is on the agency of non-human actors grows parallel to the concept of the Anthropocene but might not necessarily sit easily with it (Haraway, 2016). The production of multi-species ethnographies is helping to elevate non-humans and promote care and kinship toward a recognised Socio-natural coupling. Theories of entanglement, emergent hybridisation and enaction in the context of nature, offer an opportunity to explore through practice the process of material engagement with aesthesis being central to meaningful making. In a simple way, the concept of the Anthropocene has exposed a potential future through the recognition of our entanglement with ‘nature’.

Our entanglement with nature is a concept that is based on social and enacted ties. In reality, our entanglement has always been. It has not ‘become’ (Morton, 2014) and we have not disentangled ourselves, rather we have lost our awareness of intra-action of our species with its environment.

Intra-action, a Baradian term, ‘understands agency as not an inherent property of an individual or human to be exercised, but as a dynamism of forces’. (Barad, 2007, p. 141)

Accepting the Anthropocene as a concept as well as a defined epoch is also testament to the importance, we place on ourselves. The Anthropocene perhaps fails to properly describe our indisputable entanglement with nature. It is fatalistic in nature and as Donna Haraway quite rightly states:

‘The myth system associated with the Anthropos is a setup, and the stories end badly. More to the point, they end in double death; they are not about ongoingness. It is hard to tell a good story with such a bad actor.’

(Haraway, 2016)

For Haraway, the Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene are all terms describing our current epoch: ‘three stories that are too big, and also not big enough’. (AURA, 2014) The ‘Anthropocene’, as Haraway states, is the proposed favourite, one that has been readily adopted by many academics and groups though, as Haraway argues, the proposed epoch might be better titled as the ‘Capitalocene’ in that it is not man alone that is causing a 6th extinction with environmental devastation on a global scale – it is the ruling ‘world-system’ as a ‘capitalist world-ecology’ (Moore, 2013). Haraway’s preferred moniker for the current epoch is The Chthulucene. Not driven by species specific impact, nor by hegemonic world systems, The Chthulucene at its heart, brings back into focus our entanglement with all things and asks the question, how will we live now? Derived from the Greek word Chthonic relating to or inhabiting what lies beneath, a word for ancient, ‘subterranean’, ‘abyssal’ (E-flux.com, 2016), The Chthulucene makes a future possible. The idea that we are entangled, a ‘hot compost’ heap of collaboration and ‘becoming-with’ (Haraway, 2016) from where all things are birthed is a positive one. The Chthulucene is a post-anthropocentric proclamation of the interconnected relations between earth, materials, humans, and non-humans.

There is joy in the Chthulucene. In her book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene there is a loud call to find the means of ‘living well’ within the troubling world we’ve accumulated. This concept eases the guilt, allows us to find better ways to inhabit our story of destruction, to adopt ongoingness rather than sitting in a chair slowly killing ourselves whilst blinkered to the wicked problems we have created yet are powerless to fix. It is this joy, as opposed to the tropes of doom that I choose to explore when making.

Chapter 2: Making-Kin at the Intersection

In a first attempt to share the concepts of connectedness and promote democracy of space by revealing a series of otherwise invisible actors through a hidden camera, I chose one of the many physical intersections where human and non-human regularly interact in the landscape. This interaction if only through aesthesis – smells, sounds and traces on the ground speaks of our connectedness. Over time, I studied the sharing of this space by both human and non-human (Fig 1) and collected evidence of how each actor influences each other’s behaviour: How humans are avoided, how the birds steal the twine for nesting, where the badgers reroute to avoid tractors for instance. Connecting us through one camera lens over a 24-hour period, my aim was to direct a spotlight toward connectedness through space-time highlighting the union of things through space and over time. Making-kin is central to this piece as is the potential to uncover tangible entanglements.

Fig. 1, Mapping the Intersections (2021)

Over a period of a few weeks, I logged transient and geomorphic changes in the landscape where there was movement and the presence of non-humans. Each line represents the traces of paths created over time. Transient dew lines are mapped with dashed lines with the black dots highlighting intersections where ‘we’ were copresent through time. The intersection I chose to film for the project ‘One Small Space through Time’(see Fig.2) is highlighted with a red arrow..

By investigating intersections of entanglement, there is an opportunity to illuminate the perceived-invisible or ignored socio-natural relations. Focussing on landscapes where affordances, agents and their traces in the landscape become the embodiment of the narratives of the human and non-human lives that have shaped them. In creating a union of actors within a given space over time there is an opportunity to reveal otherwise hidden connections with the aim to add value to the environment.

To re-value our environment, the actors within it and our connectedness with it, requires an understanding and appreciation of the various modes of socio-natural relations with non-human species and recognition of our connectedness despite the uneven power relationships illustrated as a signature of the Anthropocene.

In practice, the imperceptible worlds where entanglement exists are manifested through geomorphic changes in the landscape, hyperobjects, described by Timothy Morton as interrelated interconnected phenomenon too big to perceive (Morton, 2018), and through subjects that lie beyond our immediate habitualised and temporal experience such as cause and effect.

Artist, Alma Heikkila opens our eyes to a similarly invisible and interdependent world where the human is occupied by microscopic entities. Seeking to highlight the human dependency on invisible (to us) agents who influence, and co-depend on us, Heikkila uses paint and scale to visualise the concept of ‘mutualistic symbiosis’. Captioning this work, she writes:

‘From the level of the microscopic microbial ecosystems that reside within us (and make us), to the myriad macro-scale environmental ecosystems within which we reside and depend on (and make) – we’re interdependent/-existent: there’s no surrounding medium.’ (Heikkila, 2019)

Fig. 2 Found Living in darkness. (2020).

Heikkila focusses on the interdependence of ecosystems through a macro lens revealing an invisible world beyond normal human perception. In order to show these invisible mechanisms, Heikkila uses her ground as if it were a microscope and enlarges a world of symbiotic interdependencies between the organic and inorganic. Perhaps as an innate recognition of our microscopic relationships, the resulting work is visually familiar.

Widening that macro horizon through the experiment titled ‘’SpaceLog’ I hoped to encompass those connections that are rendered invisible only through place and time. There is familiarity in this image too – we can all name the actors in this frame – yet the strategy, also employed in Heikkila’s work is to defamiliarise – to make strange the scene in order to see the world afresh.

Fig. 3 One Small Space Through Time. A digital composite of human and non-human actors passing through an intersection over a 24-hour period. Filmed with a trail camera hung on a branch (2022)

Viktor Shklovsky, considered one of the leading figures in the Formalist movement introduced the concept of defamiliarisation in his most famous essay ‘Art as Technique’. In her thesis on the subject, Elizabeth Romanow explains that the aim of defamiliarisation is to ‘set the mind in a state of unpreparedness, to put into question the conventionality of our perceptions. By ‘making strange,’ the artist forces the reader or viewer’s mind to rethink its situation in the world.’ Romanow, E. (2013).

To force a double take and see the world afresh as if for the first time is a powerful tool in the promotion of conservation. Providing the viewer with new perspectives, to connect in a new way, to make visible that which has become invisible through familiarity is a technique found throughout the arts and commercially in marketing and design. The works of Duchamp, and Banksy, with a visual inclination toward the postaesthetic, find their potency in defamiliarisation. Duchamp a master at provocation and controversy attempted to provoke questions of what art is and in doing so, inspire change. His ideas worked on the basis that defamiliarisation would spark questions and reflection. Through the use of familiar cultural symbols, satire, humour, and space, both Duchamp and Banksy force the viewer to rethink their position in the world.

Fig. 4 La Joconde/L.H.O.O.Q., (1919)

Drawing together the themes of entanglement and making-kin with strategies of defamiliarisation and provocation is the work of Tania Kovat.

Kovat writes:

‘The main focus of my work is how art mediates and communicates our experience of what we call Nature. I think of Nature as a set of interconnected processes and systems rather than things or places. My work starts from subjective experiences and perceptions, it is an exploration of the Self. The space of particular landscapes help me access a sense of self. All art works are acts of communication but my first audience is that conversation with myself.’ (Kovats 2019).

Kovats work delves into nature, geological force and landscapes with her concepts mostly resolved through sculpture and installation. There is a weight and physicality to the works and at times she is controversial or shocking. ‘Crow’ is an example of this where initial shock gives way to defamiliarisation.

Fig. 5 Crow, (2021)

‘The animals are usually portrayed in a lifelike state for the purpose of study or triumphant celebration. By contrast, Kovats has preserved animals that are common in Britain, and they have been stuffed in the positions in which they were found by the side of the road.’ (Invisible Dust, n.d.)

Summary

In adopting the idea of the Chthulucene as well as an emphasis on connectedness, entanglement, and kin alongside Morton’s concept that ‘we are nature’, there comes a duty to practice with hope: If we have hope, we can find better ways to inhabit our story of destruction, to adopt ongoingness. Bringing hopeful discourse to an arena of ‘wicked’ problems where our species feels able to move forward is a must for conservation efforts. The importance to conservation of what Haraway describes as ‘ongoingness’ and ‘staying with the trouble’ cannot be over emphasised. Is there any other way help our species get out of the chair and practice living well?

Haraway evangelises that ‘making-kin’ with the ‘more-than-human’ world is an urgent ethical responsibility (Haraway 2018). As a linchpin to my work, connecting non-human to human through space-time has provided a problem to be solved through a series of conceptual and technical experiments. The resulting work is a conscious union of the themes and strategies discussed in this study. The work, in an effort to promote making-kin and with efforts to defamiliarise the viewer, reveals through the portal of a device, a previously unknown intersection where time and place collide. This installation is to be viewed in real-time on a smart device where the viewers reality is augmented by those who have previously occupied the space. The ‘virtual re-connection’, is programmed to recognise the landscape it is in. The software then creates a memory gallery of photos and video filled with actors once present in that position and on that stage to form the ‘SpaceLog: Intersection of Kin’.

Fig. 6 Video stills of the augmented reality experience ‘Intersection of Kin’. This still is taken directly from a smart device. The operator pans the screen around the area to seek out the position of those actors with whom it has previously shared the space. (2022)

Throughout the production of this study and artworks, there is an emphasis found in both theme and strategy with process and technique finding themselves in a somewhat postaesthetic 2nd position. Many questions arise from this most especially regarding dissemination: how is an audience engaged in the work and theme? Where is the balance of meaning and understanding? Does aesthetics play a part in wider dissemination?

Without dissemination, digestion of and reflection upon such critical themes and subsequent works cannot take place. Reaching this obvious yet profound conclusion offers the chance to inject purpose into future output and to explore further those themes, narratives, and outputs. Future study will delve deeper into socio-natural relations exploring the Chthulucene as an epistemic tool, where the materials, objects and actors used in the production or art works serve to facilitate knowledge.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1 Google (2021). Mapping the Intersections. [Google maps screenshot] Available at: https://www.google.com/maps/@53.7792001,-1.853051,365m/data=!3m1!1e3 [Accessed 10/12/2021].

Fig. 2 Heikkila, A. (2020). Found Living in darkness. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/323210/alma-heikkilnot-visible-or-recognizable-in-any-form/ [Accessed 3 Jan. 2022].

Fig. 3 Bowe, C. (2022) One Small Space Through Time. [digital composite] In Possession of: the author: Yorkshire.

Fig. 10 Duchamp, M. (1919). La Joconde/L.H.O.O.Q. Available at: https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/painting-of-the-week-is-la-joconde-l-h-o-o-q/ [Accessed 8 Apr. 2022].

Fig. 11 Kovats, T. (2019). Crow. Available at: https://invisibledust.com/projects/tania-kovats-unnatural-history-commissions [Accessed Apr. 13AD].

Fig. 12 Bowe, C. (2022) Video stills of ‘Intersection of Kin. [screen shot] In Possession of: the author: Yorkshire.

Fig. 7 Bowe, C. (2022) Video stills of ‘Intersection of Kin experience. [screen shot] In Possession of: the author: Yorkshire.

Bibliography

AURA (2014). Donna Haraway, ‘Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Staying with the Trouble’, 5/9/14. [online] Vimeo. Available at: https://vimeo.com/97663518.

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Blasdel, A. (2017). ’A reckoning for our species’: the philosopher prophet of the Anthropocene. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/15/timothy-morton-anthropocene-philosopher.

Cregan-Reid, V. (2019). A Symbol for The Anthropocene. [online] Available at: https://www.anthropocenemagazine.org/2019/06/a-symbol-for-the-anthropocene/ [Accessed 15 Jan. 2022].

De Groot, J. I. M., and Steg, L. (2009). Mean or green: which values can promote stable pro-environmental behavior? Conserv. Lett. 2, 61–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00048.x

Dorota Golanska – Geoart as a New Materialst Practice. Intra-active Becomings and Artistic (Knowledge) Production – 2018

E-flux.com. (2016). Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene – Journal #75 September 2016 – e-flux. [online] Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/75/67125/tentacular-thinking-anthropocene-capitalocene-chthulucene/.

Fanaya, P.F. (2021a) ‘Autopoietic enactivism: action and representation re-examined under Peirce’s light’, Synthese, 198(1), pp. 461–483.

Fox, Nick & Alldred, Pam. (2019). New Materialism.

Franzen, J. (2019). What if We Stopped Pretending the Climate Apocalypse Can Be Stopped? [online] The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/what-if-we-stopped-pretending.

Gamble, Christopher N., Joshua S. Hanan, and Thomas Nail. 2019. ‘What Is New Materialism?’ Angelaki : Journal of Theoretical Humanities 24 (6): 111–34.

Gunn, D. (1984). Making Art Strange: A Commentary on Defamiliarization. The Georgia Review, 38, pp.25–33.

Guyer, Paul. 1994. ‘Kant’s Conception of Fine Art.’ The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 52 (3): 275–85.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham (N.C.) ; London: Duke University Press.

Haraway at University of California, Santa Cruz on 5th September 2014, available at https://vimeo.com/97663518 (last accessed 18th September 2015).

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time. United States: Stellar Books.

HODDER, I., 2014. The Entanglements of Humans and Things: A Long-Term View. New Literary History, 45(1), pp. 19-36,153.

Ingold, Tim. 2020. ‘Meeting Art with Words: The Philosopher as Anthropologist.’ Adaptive Behavior, November, 1059712320970672.

Invisible Dust. (n.d.). Tania Kovats – UnNatural History Commissions. [online] Available at: https://invisibledust.com/projects/tania-kovats-unnatural-history-commissions [Accessed 12 Feb 2022].

Kimmerer, R.W. (2017). The Covenant of Reciprocity. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Religion and Ecology, pp.368–381.

Kovats, T. (2018). Mediating between Nature and Self – Interalia Magazine. [online] Interalia Magazine. Available at: https://www.interaliamag.org/interviews/tania-kovats/.[Accessed 10 Feb. 2022].

Leonard, N. (2020). The Arts and New Materialism: A Call to Stewardship through Mercy, Grace, and Hope. Humanities, 9(3), p.84.

Moore, J.W. (2013). Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Part III. [online] Jason W. Moore. Available at: https://jasonwmoore.wordpress.com/2013/05/19/anthropocene-or-capitalocene-part-iii/ [Accessed 9 Jan. 2022].

Mottershead D., Pearson A., Farres P., Schaefer M. (2019) Humans as Agents of Geomorphological Change: The Case of the Maltese Cart-Ruts at Misraħ Għar Il-Kbir, San Ġwann, San Pawl Tat-Tarġa and Imtaħleb.

Morton, T. (2018). Dark Ecology : for a logic of future coexistence. Columbia University Press.

Morton, T. (2009). Ecology without nature : rethinking environmental aesthetics. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press.

Newton, K. M. 1997. ‘Victor Shklovsky: ‘Art as Technique.’’ In Twentieth-Century Literary Theory: A Reader, edited by K. M. Newton, 3–5. London: Macmillan Education UK.

Olivos-Jara, P., Segura-Fernández, R., Rubio-Pérez, C. and Felipe-García, B. (2020). Biophilia and Biophobia as Emotional Attribution to Nature in Children of 5 Years Old. Frontiers in Psychology, 11.

Reiss, J.H. (2019). Art, theory and practice in the Anthropocene. Wilmington, Delaware, United States: Vernon Press.

Rittel, H.W.J. and Webber, M.M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Berkeley: Institute Of Urban And Regional Development, University Of California.

Rogers, K. (2019) ‘biophilia hypothesis’, Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/science/biophilia-hypothesis.

Romanow, E. (2013). Aesthetics of defamiliarization in Heidegger, Duchamp, and Ponge [online] Available at: https://stacks.stanford.edu/file/druid:cj591yd1063/eDiss-augmented.pdf.

Roc Jiménez de Cisneros. n.d. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://lab.cccb.org/en/author/roc-jimnez-de-cisneros-banegas

World Economic Forum. (n.d.). Over half your body isn’t human. [online] Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/04/human-body-cells-microbiome/.

Wicaksono, Singgih. (2020). VISUAL STRATEGIES OF CONTEMPORARY ART: A Case Study of Banksy’s Artworks. Journal of Urban Society’s Arts. 7. 9-14. 10.24821/jousa.v7i1.3924

Wilson, E.O. (2021). E. O. WILSON : biophilia, the diversity of life, naturalist. S.L.: Library Of America.

www.torch.ox.ac.uk. (n.d.). Metaphysics of Entanglement. [online] Available at: https://www.torch.ox.ac.uk/metaphysics-of-entanglement#:~:text=Entanglement%20phenomena%20can%20generally%20be [Accessed 13 March. 2022].